Grief is deeply personal and unique to each individual, and manifests differently for everyone, yet as a universally experienced emotion, there are some commonalities that can help us identify patterns to help our healing process.

Regardless of the cause of your grief, it’s crucial to find effective strategies to navigate through this challenging emotion. Whether triggered by the death of a loved one, the end of a relationship, job loss, or even the death of a dream, grief is an emotion most of us will encounter at some point in our lives.

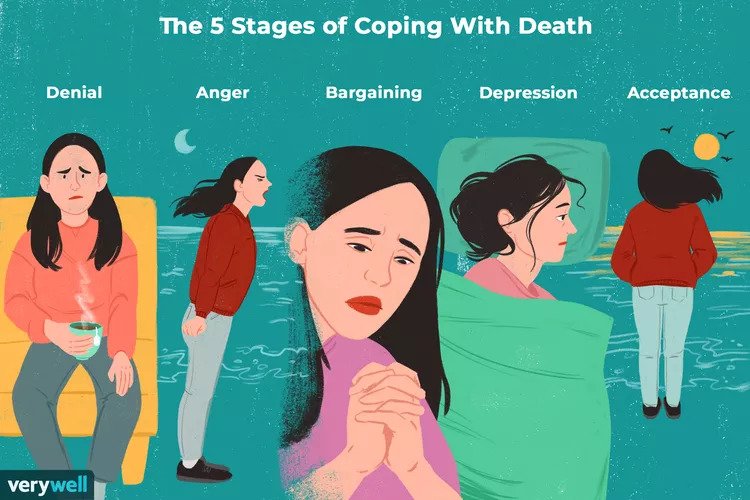

The Kübler-Ross Model, popularly known as the Five Stages of Grief, was introduced by Swiss psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross in 1969. This model outlines the progression of emotions that individuals often experience when faced with significant personal loss or change. While everyone’s journey through grief is unique, these stages serve as a general framework to understand the complex emotions we face.

Just as the Kübler-Ross Model seeks to categorize and understand the emotional roller-coaster of grief, art serves as a tangible manifestation of these raw emotions. When words fail, or emotions become too overwhelming, art becomes a refuge, a place where the bereaved can confront their pain, find a semblance of understanding, and even derive a sense of purpose from their loss. Through the act of creation, individuals not only memorialize their loved ones or lost experiences but also provide comfort and hope to others navigating grief. In this way, art and the Kübler-Ross Model intersect, illuminating the universal human experience of loss, healing, and eventual acceptance.

Let’s delve into the five stages of grief and explore how art can aid in navigating this challenging path.

Understanding the 5 Stages of Grief

Dr. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, a notable psychiatrist, introduced the five stages of grief in her groundbreaking 1969 book, “On Death and Dying.” Let’s see how Kübler-Ross & Kessler begin their book on grief:

“The stages […] were never meant to help tuck messy emotions into neat packages. They are responses to loss that many people have, but there is not a typical response to loss, as there is no typical loss. Our grief is as individual as our lives.

The five stages – denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance – are a part of the framework that makes up our learning to live with the one [or what] we have lost. They are tools to help us frame and identify what we may be feeling. But they are not stops on some linear timeline of grief. Not everyone goes through all of them or goes in a prescribed order.

Our hope is that with these stages comes the knowledge of grief’s terrain, making us better equipped to cope with life and loss.”

Let’s turn back to the wise words of Kübler-Ross & Kessler as they write about denial, the first stage of grief:

As you read, see what resonates with you. Where do you find yourself within their words? Where don’t you? Are you able to move towards recognising and naming some of your feelings as denial? Great all your responses with acceptance, curiosity and compassion.

“When we are in denial, we may respond at first by being paralyzed with shock or blanketed with numbness. The denial is still not denial of the actual death [or loss], even though someone may be saying, “I can’t believe he’s dead.” The person is actually saying that, at first, because it is too much for his or her psyche.”

“This first stage of grieving helps us to survive the loss. In this stage, the world becomes meaningless and overwhelming. Life makes no sense. We are in a state of shock and denial. We go numb. We wonder how we can go on, if we can go on, why we should go on. We try to find a way to simply get through each day. Denial and shock help us cope and make survival possible. Denial helps us to pace our feelings of grief. There is a grace in denial. It’s nature’s way of letting in only as much as we can handle.

These feelings are important; they are the psyche’s protective mechanisms. Letting in all the feelings associated with loss at once would be overwhelming emotionally. We can’t believe what has happened because we actually can’t believe what has happened. To fully believe at this stage would be too much.”

“The denial often comes in the form of our questioning our reality: Is it true? Did it really happen? Are they [is it] really gone?”

“People often find themselves telling the story of their loss over and over, which is one way that our mind deals with the trauma. […Then] you begin to question the how and why.”

“The finality of the loss begins to gradually sink in. She is not coming back. This time he didn’t make it. [Life will not be the same again]. With each question asked, you begin to believe they are really gone.

As you accept the reality of the loss and start to ask yourself questions, you are unknowingly beginning the healing process. You are becoming stronger, and the denial is beginning to fade. But as you proceed, all the feelings you were denying begin to surface.”

According to her model, individuals typically progress through the following stages when grappling with loss:

Denial

Description: Denial is the first step in dealing with grief. It helps us cope when we’ve lost someone or something important. The initial shock of the loss can be overwhelming, making it difficult to believe or accept the reality. Denial acts as a buffer, allowing individuals to numb their emotions.

During this stage, the world can seem confusing and overwhelming. Life might not make any sense, and we may feel shocked and numb. We wonder how we can go on, if we can go on, and why we should go on. Denial and shock help us handle our feelings bit by bit. It’s like a safety net that keeps us from feeling too much at once, protecting us from the immediate shock.

As we start to accept the loss and ask questions, we begin to heal, and the denial starts to fade. But as we move forward, all the feelings we were avoiding start to come to the surface.

Art’s Role:

Creating art during this stage can act as a medium to express disbelief and incomprehension. Drawing or painting the event or emotions felt can make it more tangible, helping individuals confront and acknowledge their feelings.

Anger

Description: As the protective effects of denial begin to wear off, the pain resurfaces, and it’s not uncommon for it to be redirected and expressed as anger. This anger can be aimed at oneself, others, or the situation at large.

Anger can act like a bridge that connects us to something when everything else feels disconnected. It gives us a way to hold on when we feel lost.

Anger is a natural part of healing. It’s okay to feel angry, even if it feels like it’s never-ending. When we let ourselves feel and express anger, it starts to go away, and we start to feel better. Underneath the anger, there are other feelings we’ll get to eventually, but anger is the one we know best. Anger can be directed at different things and people, including ourselves and even a higher power like God.

Art’s Role:

Art provides a safe outlet to channel and release anger. Aggressive brush strokes, bold colors, or even sculpting with clay can serve as constructive ways to vent frustration and anger.

Bargaining

Description: During this stage, individuals often find themselves trapped in a maze of “what if” and “if only” statements. There’s a desire to regain control, leading to attempts to make deals with higher powers or fate.

Before a loss, we sometimes make promises or wish for things to be different. We might say, “Please, if you let my loved one live, I’ll never be mad at them again.” After a loss, we may try to make deals in our heads, like, “What if I spend the rest of my life helping others? Can this all be a bad dream?” We get caught up in “If only…” or “What if…” thoughts. We want life to go back to how it was, to have our loved one back. We might even feel guilty, thinking we could have done something differently. We try to avoid feeling the pain of the loss. It’s like we’re stuck in the past, trying to find a way out.

Art’s Role:

Journaling or creating narrative-based artworks can be beneficial. Through storytelling, individuals can explore different outcomes, allowing them to confront and process their feelings of helplessness.

Depression

Description: After bargaining, we start to feel really sad. This sadness might seem like it’ll never go away. But it’s important to know that feeling this way is normal when we’ve lost someone important to us. We might want to withdraw from life and feel like there’s no point in going on without our loved one. This kind of sadness is okay, and it’s not a sign that something is wrong with us. It’s just part of the process of healing. It’s like a deep fog of sadness that hangs over us for a while.

When we fully realize that our loved one isn’t coming back, it’s natural to feel this way. It’s a period of reflection, sorrow, and often isolation. It may not seem so when we’re experiencing it, but it’s an essential step in healing.

Art’s Role:

Engaging in art can serve as a form of distraction, providing moments of relief from the overwhelming sadness. Moreover, creating somber and melancholic pieces can offer a way to visually represent and validate one’s feelings.

Acceptance

Description: This stage doesn’t imply happiness but rather an acceptance of reality. Acceptance doesn’t mean we’re okay with what happened. Most people never feel completely okay with losing someone they love. It’s about recognizing that our loved one is gone for good and that this is the new reality we have to live with. We won’t ever like it or make it okay, but we learn to live with it. It becomes the new normal. At first, we might want to hold on to the way things were before our loved one died. But as we go through the process, we see that we can’t go back to the past. It’s been changed forever, and we have to adapt. We learn to reorganize our lives and relationships.

Acceptance can mean having more good days than bad ones. We start living in a world where our loved one is no longer there. Instead of avoiding our feelings, we listen to our needs, and we move forward, grow, and connect with others.

We can’t replace what we’ve lost, but we can build new connections and find new meaning in our lives. It takes time, but it’s possible. Individuals come to terms with the loss, understanding its permanence, and start to move forward.

Art’s Role: Art can act as a testament to resilience and healing. Creating pieces that signify hope, rebirth, or new beginnings can be therapeutic, marking the journey from grief to acceptance.

To Wrap it up:

Grief is a complex, non-linear journey, and while the Kübler-Ross Model provides an interesting, helpful framework to comprehend it, it’s essential to remember that everyone’s experience is unique.

Art, with its boundless forms and expressions, offers a therapeutic channel to navigate through these tumultuous emotions. Whether you’re an artist or an admirer, turning to art during times of grief can be a comforting and healing experience.

For those wanting to lean into art during their grief, Laurie Copmann’s “The Family Tree the Night of the Storm” is an excellent choice. The book delves into the emotional complexities of dealing with loss, offering readers not just a story but a lifeline. It’s a resource that counselors and grief camps have turned to, time and again, to help people find their way back to light. Through intricate fabric illustrations and a compelling narrative, Laurie Copmann has created a world where every reader can find a piece of themselves.